We caught up with Murat Harmanlikli, a photographer who masterfully distills fleeting moments into compelling visual narratives. With a foundation in film photography before embracing digital, he has developed a keen ability to balance instinct with meticulous composition, capturing the subtle interactions between people, places, and time.

Viewing photography as a powerful storytelling medium, Harmanlikli draws inspiration from literature and the rhythms of everyday life, transforming ordinary scenes into evocative works of art. In this interview, he shares insights into his creative philosophy, artistic process, and the perspectives that shape his approach to photography.

Murat, every artist has a story behind their craft. Can you walk us through how you first got into photography? Was there a defining moment that made you realize this was something you wanted to pursue seriously?

Truthfully, there was no special or specific moment when I got into photography. It all started when I bought a camera during my university years, and my interest in photography increased over time. But I want to say that I have always been a person who is in love with literature since my early ages. I think that all the books I read as a child by Jules Verne, R.L.Stevenson, Daniel Defoe, Jack London, etc. enriched my imaginary world and improved my ability to think visually. Therefore, I strongly believe that it was not a coincidence that I sooner or later got acquainted with photography.

Every photograph carries an intention, whether it’s capturing raw emotion, a fleeting moment, or a carefully composed scene. How do you approach storytelling in your work, and what elements are most important to you when framing a shot?

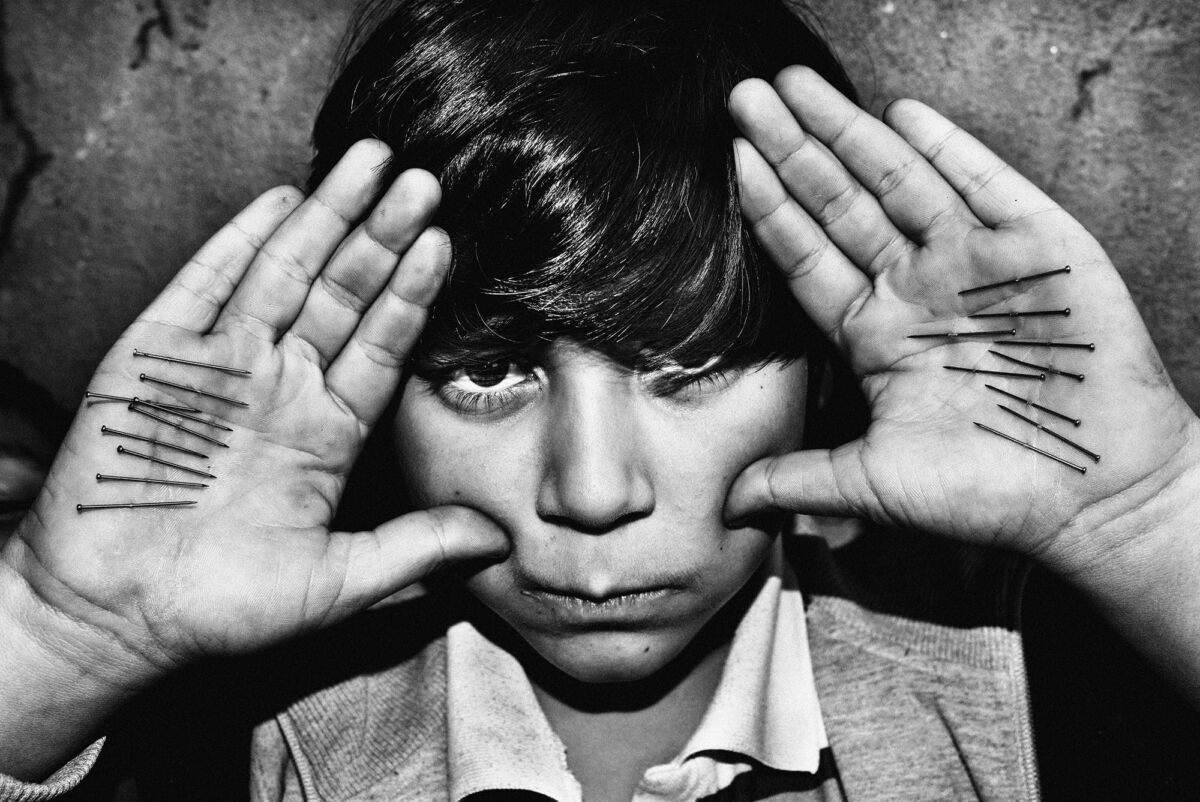

I divide my photography journey into two phases. The first phase was when I had just started photography, chasing after images that I thought were beautiful (visual impressions of books I read, music I listened to, and movies I watched). I was taking random photos at the time without thinking too much. Photography was, and still is, more of an escape, a way to get away from the stresses of daily life and my struggle with depression. It helped me breathe, it healed me. Over time, as I started taking photography more seriously and thinking deeply about it, I began to value storytelling that fundamentally revolves around people. I have always believed that a photograph is not only about what it shows but also about what it conceals and the emotions it evokes beyond the frame. In this narrative process, I have prioritized shaping my own interpretation, my unique signature. Throughout my photographic journey, I have believed that the stories I gather from the world around me come together to form my own story. So, to answer your question—what I seek in every photograph is to tell my own story. When composing a frame, I pay close attention to elements such as light, angles, reflections, shadows, framing, supporting elements, colors, tones, and symbols. The placement, balance, and proportion of all these components within the frame are like a mathematical equation. However, when shooting on the streets, I must see and arrange these elements as quickly as possible. That’s why I compare the pre-shooting process in street photography to chess—it requires strategy, foresight, and planning. But the act of shooting itself is more like backgammon—where split-second decisions, chance, and reflexes come into play.

While gear doesn’t define a photographer, it does influence how a moment is captured. How do you select your equipment, and do you believe your choice of tools affects the way you approach a subject?

I have never been a gear-focused person. For a photographer, a camera is merely a tool—a means to an end, which is the photograph itself. It is the eye behind the viewfinder that truly captures the image. Expensive equipment doesn’t make you more talented, more knowledgeable, or more certain of what you want to express.When taking a photograph, I want to be as close to the scene as possible, fully immersed in it, yet remain invisible. For this reason, I prefer using a small camera with wide-angle lenses—28mm and 35mm. When I first started photography, I used a 50mm lens, but in recent years, I have exclusively relied on the lenses I just mentioned. I believe that working with minimal gear allows me to move freely, react quickly, and focus entirely on the story unfolding in front of me, rather than being distracted by technical concerns.

The post-processing stage allows photographers to refine their vision. What’s your philosophy on editing? Do you prefer a natural approach, or do you see post-production as a way to enhance the artistic direction of your images?

My approach to editing is centered around staying true to the essence of the moment I captured. I see post-processing as a way to refine the mood and emotions present in the image rather than altering them completely. I prefer a natural approach, where adjustments in color, contrast, and light serve to enhance what is already there. However, I also believe that editing is an extension of a photographer’s artistic voice—when used thoughtfully, it can deepen the storytelling aspect of an image. For me, the goal is always to preserve the authenticity of the scene while subtly guiding the viewer’s perception toward the emotions and narrative I want to convey.I started photography with analog cameras and worked exclusively with them for about 17–18 years. During the last 10 years of that period, I had my own darkroom at home. Since I saw analog photography as a complete process—from loading the film into the camera to making the final print—I was responsible for every step in between. In the darkroom, I used multigrade paper and preferred strong contrast in my prints. I shaped each photograph according to my artistic intent, deciding whether to retain or sacrifice details in the blacks and whites. I frequently used burning and dodging techniques, always pushing my prints to achieve the highest possible contrast. When I transitioned to digital photography, my approach remained the same. Now, I work with RAW files, applying the same techniques I once used in the traditional darkroom. For me, the process of interpreting a raw image, adjusting light and shadow, and defining contrast is still an act of creation. In this sense, post-processing is not an artificial intervention but a means of revealing the soul of the photograph and completing its story.

Staying creatively engaged can be challenging over time. How do you keep yourself inspired and avoid creative stagnation? Do you have any specific routines, experiences, or sources of inspiration that help refresh your perspective?

For me, photography is not just a production process, but also a way of understanding, exploring, and connecting with the world. That’s why the most important way for me to keep myself fresh as a creator is to always be in a state of observation and remain open to new experiences. I have been taking photographs for many years, and now photography has become an inseparable part of my life. It’s always in the back of my mind, like a constantly running app, processing continuously in my head.Even when my camera is not with me, I capture frames with my eyes. In the monotony of daily life—whether I’m waiting in line, traveling, or getting lost in a mundane moment—this habit has become both a game and an exercise for me. I’ve been doing this for so long that now when I pick up my camera, I can think of and capture scenes more quickly.At the same time, I always carry a photo project in my mind. I plan these projects just like a novelist would: first, I create a framework, set sections, extract keywords, and then try to produce the photographs that complete the story. This method helps me avoid creative stagnation.Still, if I ever feel stuck, I turn to the works of my favorite photographers. I study their photographs to understand the elements that make their frames special. In addition, reading novels is a great source of inspiration for me. Novels are essentially literary texts that create visual worlds; they use words to create images and make us visualize scenes in our minds. In this way, novels help me pre-visualize the photographs I want to take.Photography is not just about capturing an image; it is a way of understanding, feeling, and telling the world.

Constructive critique is crucial for any artist’s growth. How do you approach feedback, and do you actively seek it out? Have there been any critiques that significantly influenced the way you create?

First and foremost, I don’t believe in absolute rights or wrongs in photography—or in any form of art, for that matter. Art is a reflection of the unique and consistent path one chooses to follow. In this sense, neither positive nor negative critiques play a primary role in my creative process. I say this as someone who has been engaged in photography for many years, constantly thinking, reading, and researching about it. The successes and mistakes in my work are entirely my own. I embrace them because they are what shape me and my artistic journey.John Berger, in Ways of Seeing, states: “What we see is influenced by what we believe or think.” He further adds: “We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves.”These words perfectly encapsulate my approach to critique. Each of us has a different relationship with the world, with events, with people, and with objects. Therefore, I don’t believe that what holds true for one person must necessarily hold true for another. This is why I don’t put much stock in superficial or mediocre critiques. Instead, I value meaningful exchanges—how people feel when they look at my photographs, what emotions my work evokes in them. Because, in the end, this is my world. My success is measured by how well I can convey this world through my own distinct perspective. If I can achieve that, then I consider myself successful.

Looking ahead, are there any projects, themes, or locations that you’re particularly excited to explore? What new challenges or ideas are driving your work at the moment?

These days, I am working on my project “Istanbul, in the Flux of an All-Embracing Moment”. This project consists of seven sub-sections, inspired by the seven hills of Istanbul. Each section will include 20 to 25 photographs, making a total of around 150 images. Every sub-section, along with the main title, will have its own short story. In this way, I aim to create a kind of visual novel of Istanbul.I am working on this project in color, which is a new experience for me. Since I first started photography, this is the first time I am shooting in color. Once I complete this project, I plan to embark on another one, inspired by Georges Perec’s novel Un Homme qui Dort (A Man Asleep), which I intend to shoot in black and white with flash.If you’d like, I can share the introductory text I have written for “Istanbul, in the Flux of an All-Embracing Moment”:”It was to study at university that I first came to İstanbul. I was very excited that I was going to discover the strangeness, chaos, and anarchy of Istanbul, which doesn’t fit into any classification or discipline. Wandering around the historical peninsula, the place that most reflects the melancholic spirit of the city stuck between the West and the East, caught between the past and the present was my greatest pleasure. I used to leave myself among the huge crowds and drag along from one place to another. I used to roam around the labyrinth-like narrow streets, watch people in the courtyards of historical mosques, look at the shop windows full of all kinds of bizarrenesses, and enter the musty and damp-smelling passages and bazaars with curiosity. Each corner of the city was making me feel like I was beyond time.Now, years later, I am working on my long-term project about Istanbul. With my camera in my hands, I am walking in this hustle and bustle again step by step like a flaneur. I try to tell stories gathered from the embracing moments of Istanbul. Just like years ago, children are running after pigeons, the mannequins in front of the shops are looking into my eyes as if they are asking me for help, and the giant posters on the walls of the buildings are still watching me like Big Brother. For an instant, I lose my sense of time: Am I in the present, or am I still that young man who came to Istanbul for the first time? Then, as the sound of the call to prayer from a nearby mosque mingles with the cacophony of the city, the verses of Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, a Turkish author, silently pass through my mind: ‘I am / not within time / Nor entirely beyond; But in the flux / Of an all-embracing, complete, indivisible moment.’”

The photography industry continues to evolve with new trends and technologies. How do you adapt to these changes, and do you see them as opportunities or challenges for photographers today?

I think I’m a bit old-fashioned when it comes to technology. I’ve never enjoyed tweaking the settings of my devices—whether it’s a computer, camera, or phone—nor do I like spending time adjusting them. When I first get a new device, I set it up according to my preferences, and from that moment on, I use it as it is. As I’ve mentioned before, I used analog cameras for many years and resisted switching to digital for a long time—until 2016, to be exact. Looking back, I realize that my reluctance was unnecessary. Transitioning to digital not only provided financial advantages but also increased my speed and efficiency, allowing me to produce more photographs. That being said, I will reiterate something I strongly believe: owning an expensive camera does not make you a better photographer. It’s more like a grown-up’s toy, and camera manufacturers are primarily focused on selling more equipment. My focus, however, has always been on taking better photographs, regardless of the tool in my hands. For me, technology is neither a threat nor a shortcut; it’s an extension of vision. Whether it’s advancements in camera technology, post-processing tools, or new platforms for sharing work, these innovations offer new ways to express ideas. However, I believe that no matter how much technology advances, the most powerful element in photography will always be the photographer’s ability to observe, interpret, and connect.

For those aspiring to build a career in photography, finding direction can be daunting. What advice would you offer to emerging photographers trying to develop their skills and navigate the industry?

With the advent of digital photography, the world has, unfortunately, turned into a visual landfill. Photography has become cheaper than free, and every day, we are bombarded with thousands of uninspiring images. On photo-sharing platforms, mediocre photographs can easily become trends, while truly good images risk being overlooked or dismissed as ordinary. In such an overwhelming sea of visuals, standing out is no easy task.I don’t consider myself in a position to give advice, but I can share what I believe for myself: No matter what I do, including photography, I strive to do my absolute best. I read, research, and push myself to improve constantly. As Balzac once said, “Let us aim high! If a man is to strike at something in the heavens, he must take aim at God.” If you are going to pursue something, aim for the highest—otherwise, you risk fading into insignificance. Becoming the best may be an impossible pursuit, but the journey itself—getting lost in the process, constantly learning, and evolving—is what truly matters.

Photography has the power to provoke thought, evoke emotion, and spark conversations. What do you hope people take away from your work, and is there a particular impact or message you strive to convey through your images?

I don’t aim to give direct messages through my photographs. Instead, I try to create images that encourage people to pause, observe, and reflect. For me, photography is not about providing answers but about raising questions. I want my images to serve as open-ended narratives, allowing each viewer to bring their own experiences and interpretations into the story. If a photograph lingers in someone’s mind, making them feel something—even if they cannot quite put it into words—then I believe it has fulfilled its purpose.”There are images that present a message so explicitly that they dictate what I should think—and I find that unsettling. I describe such photographs as tautological; they show exactly what they say and say nothing beyond what they show. In a way, I believe they insult the intelligence of the viewer, leaving no room for personal interpretation or thought.Once, someone made an observation about my photography that resonated with me deeply—one that also indirectly answers a question you asked earlier. They said, “Murat’s photographs don’t force us to go in a particular direction, but they show us the paths we might take.” I appreciated this remark because it aligns with how I approach my work.Paolo Pellegrin once said, “I’m more interested in a photography that is ‘unfinished’—a photography that is suggestive and can trigger a conversation or dialogue. There are pictures that are closed, finished, to which there is no way in.”I completely agree. As I said, Photography, for me, is not about giving answers but about opening doors—creating images that invite viewers to explore, interpret, and engage in a dialogue of their own. Thank you for these thoughtful questions and for having me. It has been a pleasure.

Website: www.muratharmanlikli.com

Instagram: https://www.Instagram.com/murat.harmanlikli

Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/mharmanlikli/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mharmanlikli

Image Credits

Murat Harmanlikli

Have a question for Murat or want to share your thoughts? Drop a comment below!

Nominate Someone: Camorabug is built on recommendations and shoutouts from the community; it’s how we uncover hidden gems, so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.