The 19th-century Victorian era, a time of industrial progress and imperial dominance, coincided with an intense fascination with ancient Egypt. Sparked by Napoleon’s conquest of the region, this obsession opened the gates to Egypt’s history for European elites, albeit with little regard for cultural preservation or respect. Mummies, the iconic symbols of Egypt’s funerary traditions, were at the center of this craze, becoming objects of desecration and commodification.

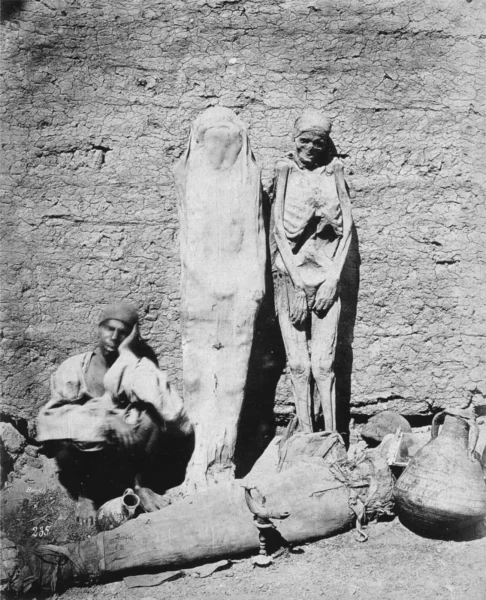

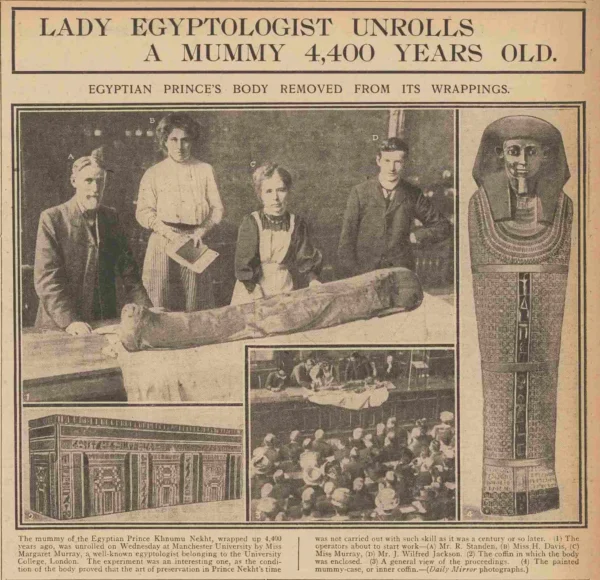

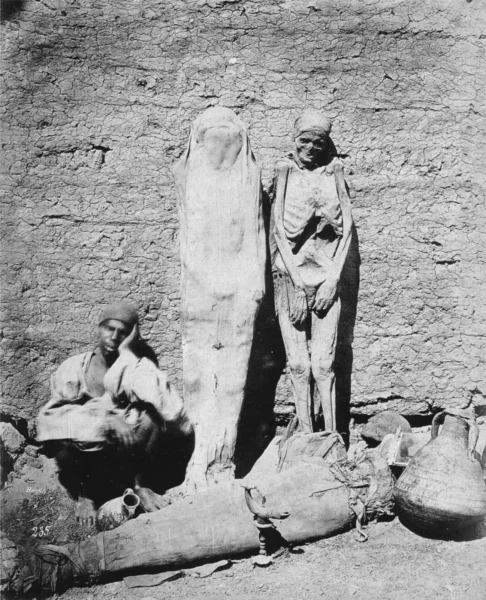

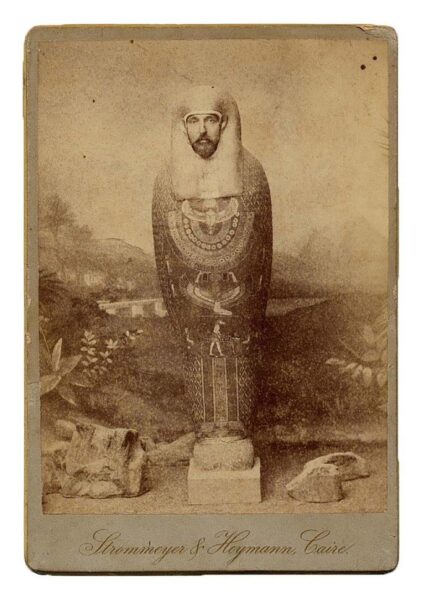

In the streets of Cairo during this period, mummies were sold openly by street vendors alongside mundane goods. These well-preserved remains of ancient Egyptians were stripped of their sacred significance and used as the centerpiece of macabre social events. Wealthy Victorians hosted what came to be known as “Mummy Unwrapping Parties.” At these gatherings, an actual Egyptian mummy would be unwrapped before an eager and cheering audience. Far from respecting the dead, these events turned human remains into grotesque spectacles for entertainment.

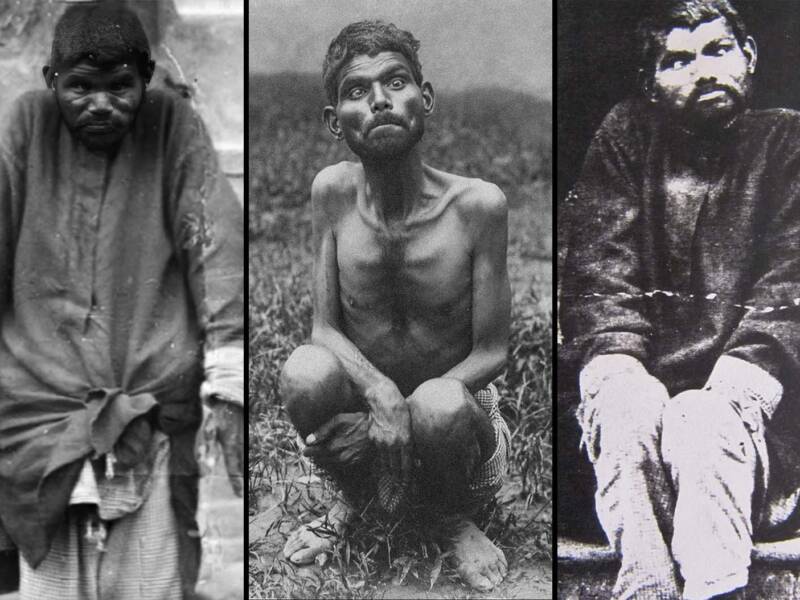

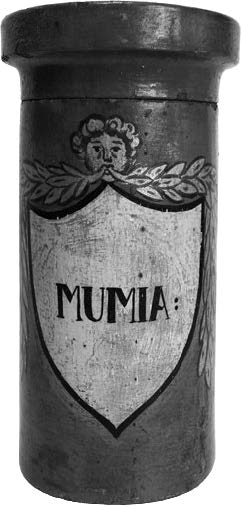

Beyond parties, mummies found their way into the realm of pseudoscience and medicine. Pulverized mummies, ground into a powder known as “mumia,” were believed to possess medicinal properties and were consumed as remedies for various ailments. The demand for mumia was so high that counterfeiters began using the bodies of beggars, criminals, and the poor, passing them off as ancient Egyptian remains.

Industrialization brought further indignities to mummies. The remains of humans and animals were shipped en masse to Europe, where they were repurposed for industrial use. Mummies were ground into fertilizer for British and German farms, stripped of their wrappings for paper production in the United States, and even burned as locomotive fuel in Egypt. Mark Twain famously wrote about witnessing this shocking use of mummies as fuel.

The art world was no less culpable in this exploitation. A pigment known as Mummy Brown, made by grinding mummified remains into powder, was a favorite among European painters. This unique color was used for shadows, glazes, and flesh tones, prized for its transparency and durability. Manufacturers openly advertised for ancient mummies to meet the demand for this pigment, which remained in production until the early 20th century, when supplies finally dwindled.

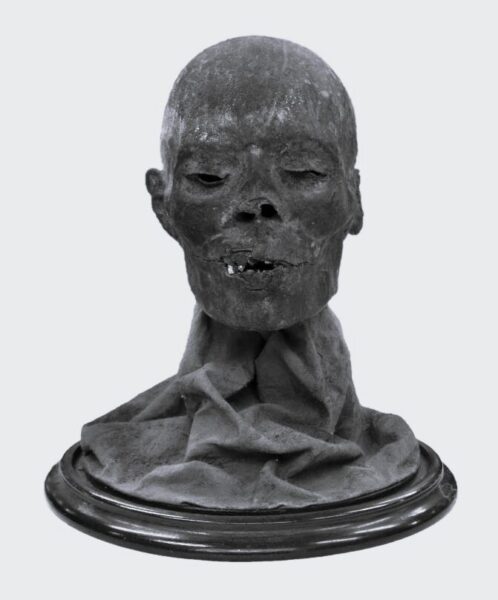

As mummies became rarer, a brisk black-market trade emerged. Wealthy tourists purchased mummies as souvenirs, while those with fewer resources could buy disarticulated remains such as hands or heads. When genuine mummies were unavailable, counterfeiters fabricated them from recently deceased bodies, treating them with bitumen and exposing them to the sun to mimic the appearance of ancient mummies.

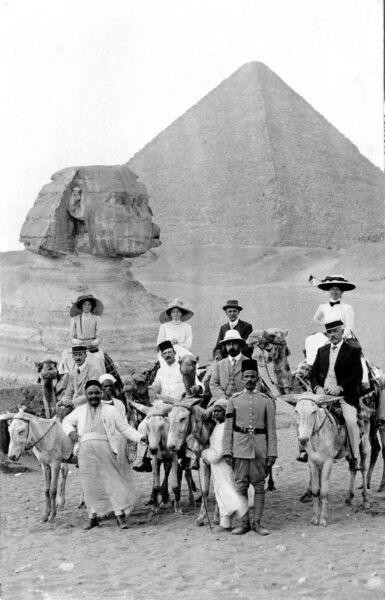

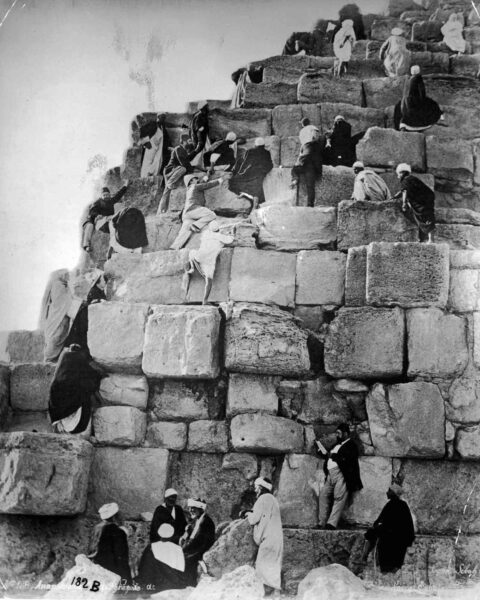

The desecration of Egyptian heritage during this period wasn’t limited to human remains. Tourists vandalized archaeological sites, carving their initials into temple walls or chipping off fragments of monuments as keepsakes. The Suez Canal’s opening in 1869 further facilitated tourism, attracting waves of visitors who often disregarded local customs and norms.

This rampant exploitation left an indelible mark on Egypt’s cultural heritage. The legacy of these actions is evident in the challenges faced today by museums and institutions grappling with the ethical implications of their collections. Many of the artifacts and mummies displayed in Western institutions were obtained through colonial looting and grave robbing.

As calls for repatriation grow louder, the need for meaningful action becomes increasingly urgent. Beyond returning artifacts, institutions must prioritize transparency, acknowledging the histories behind their collections and collaborating with source communities to ensure respectful sharing and cultural exchange.

This dark chapter serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of unchecked curiosity and colonial entitlement. It underscores the importance of treating cultural heritage with the respect and dignity it deserves, lest history repeats itself in new forms of exploitation.

The Victorian fascination with ancient Egypt may have opened the world’s eyes to the wonders of the past, but it also serves as a sobering reminder of the harm caused by cultural arrogance and greed. Let this history be a lesson to future generations: curiosity must always be tempered by respect, and the value of human history lies not in its possession but in its preservation and understanding.

- Rwanda’s Futuristic Hairstyles from the 1920s and 1930s - February 5, 2025

- How to Master Photography Basics for Stunning Shots - January 2, 2025

- Photography Exposure Triangle Explained: A Beginner’s Guide - January 1, 2025